September 2016 – Artifact of the Month

To Artifact of the Month Index

To PAF Home

~~~

Lost and Found:

Signet Ring Lost before 1789, Found 2014

Gemstone with the British Royal Coat of Arms found at the bottom of the Humphreyses’ privy. Archaeologists excavated the privy, near 3rd and Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, in advance of the construction of the Museum of the American Revolution (opening 2017). (Photo courtesy of Juliette Gerhart: Plate 4.6., AS I of Feature 16, lot 77.)

During excavations preceding the construction of the new Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia (opening April 2017), this small white gemstone was found. The roughly circular stone, measuring just 1/2 by 3/5ths of an inch (1.3cm by 1.5cm), was recovered from a privy (outhouse) located behind a house in ‘Carter’s Alley’, a minor thoroughfare that once transected the block defined by 2nd and 3rd Streets and Walnut and Chestnut Streets. The house operated as an unlicensed tavern during the time of the American Revolution. The gemstone was found among many artifacts — punch bowls, tankards, glass bottles — that related to the tavern.

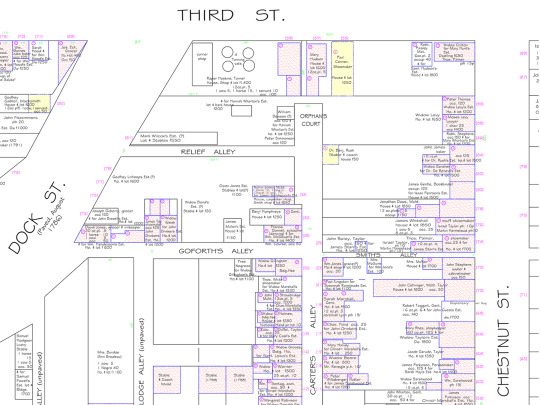

Map showing the location of Carter’s Alley.

[See a copy of the map, supplied by Independence National Historical Park, at the ‘Making the Museum’ tumbler page.]

The gemstone was engraved on one side with a design which, though worn, can still be identified as the British Royal Coat of Arms. The beveled edges of the gemstone indicate it was the central piece of a signet ring, or seal, used to stamp one’s mark in wax on a letter or document. The ring was both an element of jewelry worn by gentlemen and a tool serving the very practical purpose of sealing a document and authenticating it at a time when seals were considered more official than signatures.

The coat of arms carved on this stone consists of a central, slightly oval, shield surmounted by a crown. On the left is the lion of England standing on its hind legs, while to the right there is another figure that is traditionally the unicorn of Scotland but which is too worn in this case to identify. The shield is clearly divided into four quadrants though it is difficult to decipher the visible interior markings. Normally the quadrants consist of three horizontal lions, known as the lions passant guardant. These represent England (in the first, or upper left, quadrant and the fourth, lower right quadrant); a vertical lion known as ‘the lion rampant’ representing Scotland in the second upper right quadrant and, in the third, lower left quadrant, a harp representing Ireland. Below the shield is a banner on which would be inscribed the motto ‘Dieu et mon droit‘ – “God and my right” – adopted by the English monarch Henry V at the start of the 15th century and always present thereafter. In this case however no writing remains discernible.

Not on this specimen is a scroll motif bearing the words ‘Honi soit qui mal y pense‘ – “Spurned be he who evil thinks”, which is the motto of the Most Noble Order of the Garter. This absence suggests that while the owner of the seal had not received this Order (the highest order of chivalry) its owner was someone who would have represented the British government or the British King himself, George III.

Such rings were commonly worn on the little finger of the non-dominant hand with the image facing out. The wear pattern on this stone/seal suggests its owner was left-handed. It would seem unlikely that the stone was thrown away and so we can assume that it fell off, quite probably when the owner was actually using the privy, where it remained when the privy ceased being used in 1789. It would stay there, in the ground within the privy fill, for another 225 years until being recovered in the summer of 2014 by archaeologists from Commonwealth Heritage Group excavating on behalf of the Museum of the American Revolution.

Learn more about this archaeological investigation at Making the Museum, a tumbler feature sharing the ‘behind the scenes’ of the Museum of the American Revolution, opening in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in early 2017.

Read news coverage about the excavations (scroll to ‘Museum of the American Revolution’).

_______

This Artifact of the Month write up was contributed by Juliette Gerhard, of the Pennsylvania Office of Commonwealth Heritage Group.

by admin